In the silent auction of Ken Chivers’s estate almost forty years ago, I won the book, Fairy Tale Railroad, the story of the Mohawk and Malone Railroad in upper New York State. As my modelling interests matured, the danger of modelling New York dissipated and the book was a candidate to re-home. It was nearly given away when I moved west, and again when we emigrated for Europe; we moved back it was nearly donated and again when we were deconstructing Mt Flood; I considered selling it at three separate garage sales. Each time, I plucked it from the box of discards at the last moment. Finally we were Marie Kondoing our upstairs book collection, and I held it to my chest and decided: it is a book I love. It brings me joy, and belongs in my life.

I’ve always assumed the reason I couldn’t part with the book was because of Ken. He was a Tuesday night regular with Tom Hood, whose daughter, Ellen, was in my grade. One Tuesday while I was assembling a truck kit, I wondered what colour it should be. It was Ken who suggested that I should find a photograph of a real truck to guide my decision. The comment spurred a lifetime of prototype modelling.

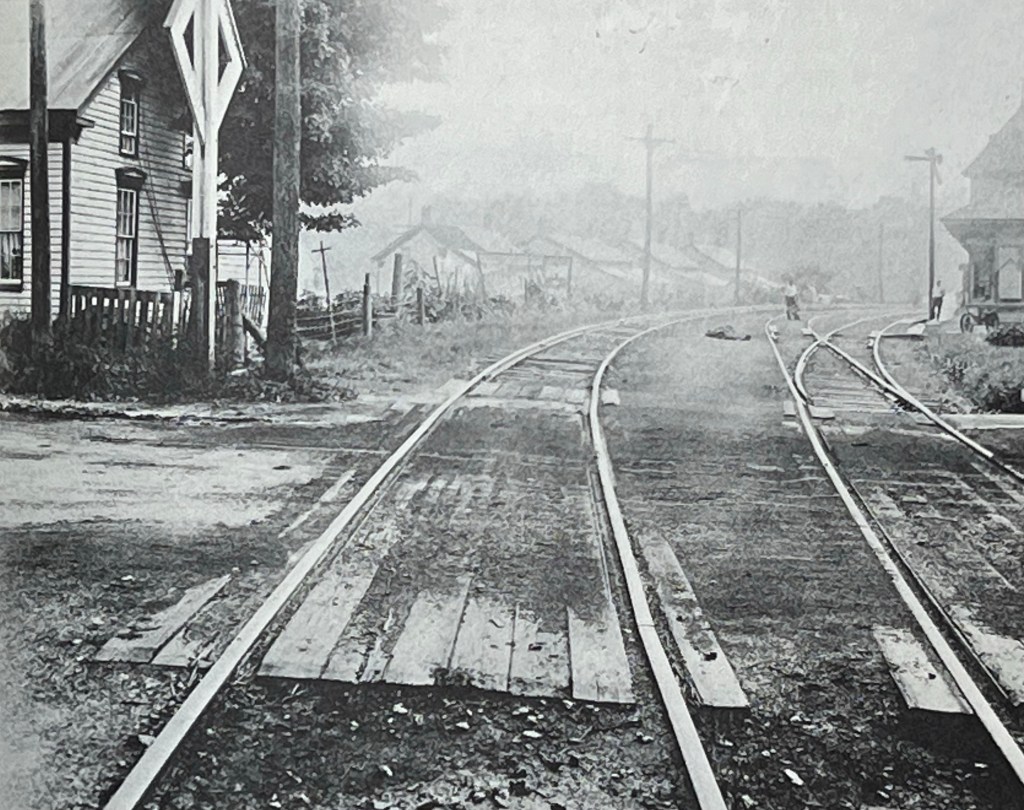

Ken’s influence might be the reason the book has survived, but in truth most of the book could go if I could keep the image below. The book falls open to this page, and I have wasted hours studying its subtle details.

It’s almost nothing to look at: just two tracks converging as they round the curve at Middleville (even the name is laughably ordinary). In the distance, as the tracks converge, a man stands right where Ted Rose would paint him, anticipating a train from behind the photographer. Houses in the distance are lost to haze, and the station is hinted, not seen. The house at the crossing is tantalizingly out of reach behind sign and tree. There is nothing to see. Nothing but atmosphere.

My friend Brian Rudko speculates that we build model railroads to revisit images that resonate with us. Some photographs, videos and indeed memories draw us in so that we are driven to recreate them in miniature.

It begs the question, though: why do some images call to me in this way? Why do you not respond the same way? What are the critical elements of the image that we must replicate in miniature to successfully revisit the image we seek?

Brian may be right, and it is images like this one that inspire and drive us to build model railroads. But without answering the next questions, we can only hope to satisfy our vision.

René, I will very quickly exceed my depth with this; I am persuaded that in images (or ideas, or experiences) that resonate within us, we perceive something that we desire to pass into and participate in. Quantifying the “something” we “long to join” is difficult because it reflects our interests, experience, inclinations, and background. The image above is encompassing of an era, and something about that piques your longings. Could it be simplicity, or perhaps the order and elegance of the architecture, or rural charm? Standing next to you looking at the same image will elicit different responses from each of us. It strikes me that this particular image is as mundane as it is idyllic. The Dutch Masters rocked the art world because they celebrated the ordinary, the commonplace. In contemporary model railroading, I’m persuaded that this is some of the genius and success of Pelle Søeborg – simple uncluttered, unforced scenes of everyday life. There is something transcendent in this scene, and I think that’s what speaks to me in so many of the things I find myself moved by as a modeler. I think that is the very basis for our desire to model – to laud, to emulate, to participate, to enter in as best we can. Thoughts?

I think you and Brian would get along very well. For myself, I don’t think I want to return to the Edwardian era, but the scene calls to me nevertheless. Maybe it echoes the many times I’ve bumped across a crossing, peering hopefully up the track, to it empty. I certainly agree, however, with your observation that simpler scenes observed well, as Pelle does masterfully, are more compelling than complex scenes.