Figures present a contentious subject for model railroaders. Some of us enjoy creating stories and cameos with groups of figures frozen in mid-swing or suspended between strides. Others prefer their figures in static poses so their lack of animation is less obvious. There are layouts teeming like the sidewalks of Manhattan and layouts as lonely as the tundra of Nunavut.

When we look at a landscape, animals and people in particular are relatively rare except in urban areas. So, for the most part, Pembroke will be sparsely populated. Pembroke Street, itself, may be the exception, but there are years of modelling ahead before I have to commit to that decision.

So far, in addition to the Ayrshire herd, there are two – a slightly oversized boy and his dog. It is tempting to portray a haying scene in the hay field, or a threshing scene in what is likely to be a wheat field adjacent to it.

Since installing the pasture a year ago, I’ve performed a simple, if unethical, psychology experiment on many visitors. After they’ve enjoyed the pasture scene for a moment, I point out that one of the cattle is looking at them. Once they find it, I then challenge them to look away. They can, but they all find that as soon as they relax, they are once again losing a staring contest with that mulish bovine.

We are hard-wired to see people and animals and assess them as threat or opportunity. Once we find them, we continue to monitor them lest that threat increase or opportunity diminish. If they are looking at us, we know they know we’re here, and even if they are plastic, that threat is more imminent. This is why it’s difficult to look away from the cow.

If, on the other hand, the person or animal is looking aside, perhaps they are looking at something else that is a bigger threat or greater opportunity. We will follow their gaze. If they are moving, or poised for motion, we will look to their projected destination for something interesting.

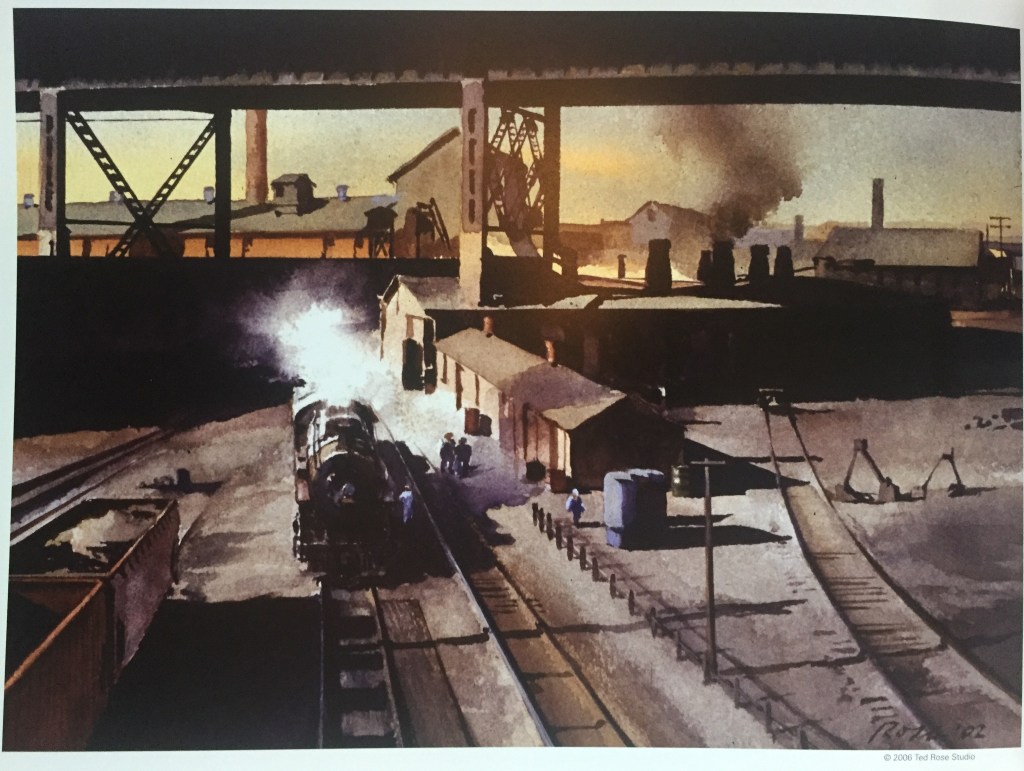

Painters and photographers understand the power of figures. Consider again these paintings by Ted Rose, which we took lessons from a few years ago. In one, the lines of the mill pull us in to trap us in the conversation at the focus of the painting. In the other, the fence pulls us to the figure, which serves to bounce our attention back and forth between the figure and the building; it makes us consider this unassuming building and ask why are they walking there.

I’ve tried to use the figures on Pembroke in the same way. The cattle are walking to the left to pull us northward toward the vibrant progressive cacophony that will be Pembroke Street. They turn and begin to follow the fence, where we find the head of the boy. I’m pleased to say that the boy forces the viewer to walk around the roundhouse for a better view, much as the monkey encouraged us to interact with the sculpture of Emily Carr. However, his original purpose was to keep us in the layout while the path and fence bee-line to the backdrop. When we do come around the roundhouse, we find he is looking at his dog, who is looking at an imaginary squirrel in the planned copse, again to the left and toward progress.

Now, like Oscar Wilde, I can resist anything except temptation. So, I may yet succumb and find a way to add a haying team to the hay field. However, if I do, they will need to serve a purpose within the composition, and support the greater story of progress and optimism that I am trying to evoke.

Oh my I enjoyed this. Thank you!

Is the implication of interaction part of thus? We’re used to how components of an operating session or scheme interact—coal from mine goes to power plant by trains—but considering how things interact within the scene. In the case of model figures not so much what are they doing (hanging laundry) but how are they doing it as part of a community with other people. Are they together?

Your observations activate so much curiosity on this end. I love the way you think about these things.

—Chris

I think I’m going to have to write a whole post as a reply. Thanks for joining the conversation, Chris.

Rene, I look forward to that post! I’m hazarding a guess that in our youth, George Sellios’ Franklin & South Manchester with its hundreds and hundreds of figures were amazing to look at in the cityscapes he created. However, after the initial overview of the details, I found all those little people to be a bit unnerving. More recently, I feel like the “less is more” view of Tom Johnson on his MRH blog has it right. When his photos are studied, cars aren’t “perpetually waiting for the train at the crossing.” Cars are parked, the roads are empty. People, if there are any, are in repose, sitting on a bench at a General Store, or leaning on a post. That gives plausibility to why something that should be moving wasn’t. In your mini scene, the boy’s tilted head and frozen pose lend credence that the dog has spied something in the grasses and they are taking a wait and see approach! I enjoy it!